One can easily misrepresent or exaggerate reality with a few select statistics and come to conveniently chosen conclusions. This doesn’t really help the conversation.

The distribution of wealth and income has become a social, economic, and political problem in recent decades. And not only in the US. But the question is why and what to do about it.

First, we should notice the timeframe of the comparison: 1980 vs. 2014. During these years there has been a massive credit bubble with low to zero interest rates and low inflation, especially over the past 16 years. This has disproportionately rewarded asset holders and debt-driven consumption and the income shares in industries associated with that, like FIRE.

The cheap credit has also led to massive investments in technology and biotech, where income levels have far exceeded those in other industries. This is not necessarily a bad thing, especially for aggregate growth, but it does have distributional consequences for wealth and income. Globalization, through outsourcing, trade and labor migration, has also served to keep labor costs low in developed nations.

So, what to make of this? I would have differences with the suggestions of the author as stated here:

Different policies could produce a different outcome. My list would start with a tax code that does less to favor the affluent, a better-functioning education system, more bargaining power for workers and less tolerance for corporate consolidation.

First, the problem with the tax code is that it creates barriers for asset accumulation for those without assets. In other words, it favors the haves over the wannabes, even if the wannabes are more deserving. So we need to reduce those barriers. Not by making it harder to get rich, but by making it harder to stay rich and idle sitting on assets that have ballooned in value through no effort on the owners of those assets. Thus, we should look more toward wealth taxes as opposed to income or capital taxes. We should also make capital taxes more progressive so that the have-nots are not doomed to remain so. Have you seen your interest on savings lately?

Second, a better functioning education system is always a deserved policy priority, but it won’t fix this income distribution problem. The cost of education is becoming prohibitive and elitism is turning top universities, where costs are in the stratosphere, into branding agents rather than educating institutions. In other words, the Ivy League degree is more valuable as a signalling device than anything a student may or may not have learned there. Thus we are biasing favoritism over meritocracy.

Third, the focus on wages and organized labor is completely misguided. Most workers in growth industries in the 21st century eschew labor unions in favor of equity participation and risk-taking entrepreneurship. Does that mean manufacturing labor has no future? Not at all. But it should be bargaining for equity in addition to a base wage. Competing solely on wages means workers are competing with the global supply of labor, which is a losing proposition for developed countries’ workers.

The inability of policymakers to see clearly how the world has changed and how ownership and control structures must adapt to the information economy leads them towards the rabbit hole of universal basic incomes, which fundamentally is a universal welfare program to support consumption. One thing we’ve learned over the past 60 years is that nobody wants welfare, but many become addicted to it. It’s not a solution or even a short-term fix.

Refer to the NYT website link to view the graphs…

Many Americans can’t remember anything other than an economy with skyrocketing inequality, in which living standards for most Americans are stagnating and the rich are pulling away. It feels inevitable.

But it’s not.

A well-known team of inequality researchers — Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman — has been getting some attention recently for a chart it produced. It shows the change in income between 1980 and 2014 for every point on the distribution, and it neatly summarizes the recent soaring of inequality.

The line on the chart (which we have recreated as the red line above) resembles a classic hockey-stick graph. It’s mostly flat and close to zero, before spiking upward at the end. That spike shows that the very affluent, and only the very affluent, have received significant raises in recent decades.

This line captures the rise in inequality better than any other chart or simple summary that I’ve seen. So I went to the economists with a request: Could they produce versions of their chart for years before 1980, to capture the income trends following World War II. You are looking at the result here.

The message is straightforward. Only a few decades ago, the middle class and the poor weren’t just receiving healthy raises. Their take-home pay was rising even more rapidly, in percentage terms, than the pay of the rich.

The post-inflation, after-tax raises that were typical for the middle class during the pre-1980 period — about 2 percent a year — translate into rapid gains in living standards. At that rate, a household’s income almost doubles every 34 years. (The economists used 34-year windows to stay consistent with their original chart, which covered 1980 through 2014.)

In recent decades, by contrast, only very affluent families — those in roughly the top 1/40th of the income distribution — have received such large raises. Yes, the upper-middle class has done better than the middle class or the poor, but the huge gaps are between the super-rich and everyone else.

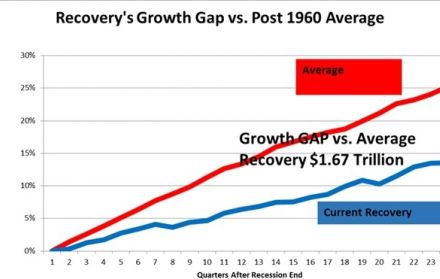

The basic problem is that most families used to receive something approaching their fair share of economic growth, and they don’t anymore.

It’s true that the country can’t magically return to the 1950s and 1960s (nor would we want to, all things considered). Economic growth was faster in those decades than we can reasonably expect today. Yet there is nothing natural about the distribution of today’s growth — the fact that our economic bounty flows overwhelmingly to a small share of the population.

Different policies could produce a different outcome. My list would start with a tax code that does less to favor the affluent, a better-functioning education system, more bargaining power for workers and less tolerance for corporate consolidation.

Remarkably, President Trump and the Republican leaders in Congress are trying to go in the other direction. They spent months trying to take away health insurance from millions of middle-class and poor families. Their initial tax-reform planswould reduce taxes for the rich much more than for everyone else. And they want to cut spending on schools, even though education is the single best way to improve middle-class living standards over the long term.

Most Americans would look at these charts and conclude that inequality is out of control. The president, on the other hand, seems to think that inequality isn’t big enough.