This article explains in greater detail a subject I addressed in a recent comment in the Wall St. Journal:

“…our macroeconomic models are wholly incapable of incorporating operational measures of uncertainty and risk as variables that affect human decision-making under loss aversion. We’ve created this unmeasurable sense of uncertainty by allowing exchange rates to float, leading to price volatility in asset markets because credit policy is unrestrained.

The idea of floating exchange rates was that currency markets would discipline fiscal policy across trading partners. But exchange rates don’t directly signal domestic voters in favor of policy reform and instead permit fiscal irresponsibility to flourish. Lax credit policy merely accommodates this fiscal fecklessness. The euro and ECB were tasked with reining in fiscal policy in the EU, but that has also failed with the fudging of budget deficits and the lack of a fiscal federalism mechanism.

The bottom line is that we do NOT have a rebalancing mechanism for the global economy beyond the historic business cycles of frequent corrections that are politically painful. The danger is we now may be amplifying those cycles.”

From Barron’s:

Currency Wars: Central Banks Play a Dangerous Game

As nations race to reduce the value of their money, the global economy takes a hit.”

Almost three generations after the Great Depression, that lesson has been unlearned. In the years leading up to the Depression, and even after the contraction began, the Victorian and Edwardian propriety of the gold standard was maintained until the painful steps needed to deflate wages and prices to maintain exchange rates became politically untenable, as the eminent economic historian Barry Eichengreen of the University of California, Berkeley, has written. The countries that were the earliest to throw off what he dubbed “golden fetters” recovered the fastest, starting with Britain, which terminated sterling’s link to gold in 1931.

This, however, is the lesson being relearned. The last vestiges of fixed exchange rates died when the Nixon administration ended the dollar’s convertibility into gold at $35 an ounce in August 1971. Since then, the world has essentially had floating exchange rates. That means they have risen and fallen like a floating dock with the tides. But unlike tides that are determined by nature, the rise and fall of currencies has been driven largely by human policy makers.

Central banks have used flexible exchange rates, rather than more politically problematic structural, supply-side reforms, as the expedient means to stimulate their debt-burdened economies. In an insightful report last week, Morgan Stanley global strategists Manoj Pradhan, Chetan Ahya, and Patryk Drozdzik counted 12 central banks around the globe that recently eased policy, including the European Central Bank and its counterparts in Switzerland, Denmark, Canada, Australia, Russia, India, and Singapore. These were joined by Sweden after the note went to press.

In total, there have been some 514 monetary easing moves by central banks over the past three years, by Evercore ISI’s count. And that easy money has been supporting global stock markets (more of which later).

As for the real economy, the Morgan Stanley analysts write that while currency devaluation is a zero-sum game in a world that isn’t growing, the early movers are the biggest beneficiaries at the expense of the late movers.

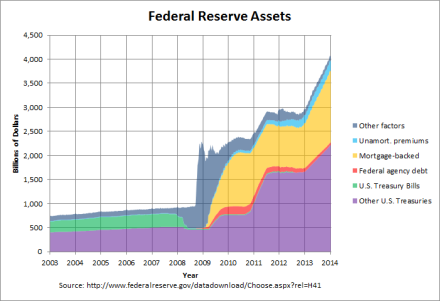

The U.S. was the first mover with the Federal Reserve’s quantitative-easing program. Indeed, it was the initiation of QE2 in 2010 that provoked Brazil’s finance minister to make the first accusation that the U.S. was starting a currency war by driving down the value of the dollar—and by necessary extension, driving up exchange rates of other currencies, such as the real, thus hurting the competitiveness of export-dependent economies, such as Brazil.

Since then, the Morgan Stanley team continues, there has been a torrent of easings (as tallied by Evercore ISI) to pass the proverbial hot potato by exporting deflation. That has left just two importers of deflation—the U.S. and China.

The Fed ended QE last year and, according to conventional wisdom, is set to raise its federal-funds target from nearly nil (0% to 0.25%) some time this year. That has sent the dollar sharply higher, resulting in imported deflation. U.S. import prices plunged 2.8% in January, albeit largely because of petroleum. But over the past 12 months, overall import prices slid 8%, with nonpetroleum imports down 1.2%.

China is the other importer of deflation, they continue, owing to the renminbi’s relatively tight peg to the dollar. The RMB’s appreciation has been among the highest since 2005 and since the second quarter of last year. As a result, China has lagged the Bank of Japan, the ECB, and much of the developed and emerging-market economies in using currency depreciation to ease domestic deflation.

The bad news, according to the Morgan Stanley trio, is that not everyone can depreciate their currency at once. “Of particular concern is China, which has done less than others and hence stands to import deflation exactly when it doesn’t need to add to domestic deflationary pressures,” they write.

But they see central bankers around the globe being “fully engaged” in the battle against “lowflation,” generating monetary expansion at home and ultralow or even negative interest rates to generate growth.

The question is: When? Bank of America Merrill Lynch global economists Ethan Harris and Gustavo Reis estimate that global gross domestic product will shrink this year by some $2.3 trillion, which is a result of the dollar’s rise. To put that into perspective, they write, that’s equivalent to an economy somewhere between the size of Brazil’s and the United Kingdom’s having disappeared.

Real growth will actually increase to 3.5% in 2015 from 3.3% in 2014, the BofA ML economists project; but the nominal total will decline in terms of higher-valued dollars. The rub is that we live in a nominal world, with debts and expenses fixed in nominal terms. So, the world needs nominal dollars to meet these nominal obligations.

A drop in global nominal GDP is quite unusual by historical standards, they continue. Only the U.S. and emerging Asia are forecast to see growth in nominal-dollar terms.

The BofA ML economists also don’t expect China to devalue meaningfully, although that poses a major “tail” risk (that is, at the thin ends of the normal, bell-shaped distribution of possible outcomes). But, with China importing deflation, as the Morgan Stanley team notes, the chance remains that the country could join in the currency wars that it has thus far avoided.

WHILE ALL OF THE central bank efforts at lowering currencies and exchange rates won’t likely increase the world economy in dollar terms this year, they have been successful in boosting asset prices. The Standard & Poor’s 500 headed into the three-day Presidents’ Day holiday weekend at a record 2096.99, finally topping the high set just before the turn of the year.

The Wilshire 5000, the broadest measure of the U.S. stock market, surpassed its previous mark on Thursday and also ended at a record on Friday. By Wilshire Associates’ reckoning, the Wilshire 5000 has added some $8 trillion in value since the Fed announced plans for QE3 on Sept. 12, 2012. And since Aug. 26, 2010, when plans for QE2 were revealed, the index has doubled, an increase of $12.8 trillion in the value of U.S. stocks.