From the WSJ:

How Congress Puts Itself Above the Law

The only way to finally end the sorry tradition of congressional exemptions is with a 28th Amendment.

By GERALD D. SKONING

For years, some have argued that we need a 28th Amendment to the Constitution providing that all members of Congress have to comply with all laws that other citizens have to obey. “Congress shall make no law,” the amendment might read, “that applies to the citizens of the United States that does not apply equally to the senators and/or representatives; and, Congress shall make no law that applies to the senators and/or representatives that does not apply equally to the citizens of the United States.”

Others apparently have faith in the high moral character of their elected officials and argue that we shouldn’t have to enact a constitutional amendment to make sure Congress follows the same laws all Americans do.

Yet history shows that is definitely not the case. Over the decades, Congress has passed innumerable statutes that regulate every aspect of life in the American workplace, then quickly exempted themselves.

In 1938, when the Fair Labor Standards Act established the minimum wage, the 40-hour workweek, and time and a half for overtime, Congress exempted itself from coverage of the law. As a result, for decades congressional employees were left without the protections afforded the rest of Americans working in private industry.

In 1964, with great fanfare, President Johnson signed the landmark Civil Rights Act, including Title VII, which for the first time protected all Americans from employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. But the law exempted Congress from its coverage, so thousands of staffers and other employees on the Hill were left with no equal-opportunity protection. Staffers could be discriminated against or sexually harassed with legal impunity.

Some will remember Bob Packwood, the former senator from Oregon who resigned his seat in 1995 under threat of expulsion for alleged serial harassment of female staffers and lobbyists. The women who alleged they had been repeatedly victimized by the senator had no legal recourse under federal law. Had Mr. Packwood been a corporate executive instead of a lawmaker, he likely would have been sued for millions.

The same blanket congressional exemption found in Title VII was contained in a total of 10 other federal statutes regulating the American workplace, including protections from age and disability discrimination, occupational safety and health rules, family and medical leave, and many other issues that Congress felt important enough to impose on American industry. These federal laws apply to all civilian employees in the U.S., except those working on the Hill.

Critics advanced the rather sensible and straightforward proposition that U.S. lawmakers should live by the same laws they impose on private employers and state and local elected officials.

Nonetheless, when the comprehensive reform of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 was passed, efforts to eliminate the exemption failed. The immunity of members of Congress from lawsuits for compensatory and punitive damages in cases of employment discrimination continued.

Instead, the federal lawmakers enacted a toothless, self-policing system whereby Congress investigated and enforced its own compliance with civil-rights laws.

Given the choice, private employers no doubt would welcome the opportunity to police themselves on matters of equal-employment opportunity. Who wouldn’t prefer self-regulation over dealing with government enforcement agencies and federal court juries considering punitive damages? However, unlike the Congress, private employers don’t have the option of self-regulation.

Pressure on Congress mounted and finally, in 1995, with Republicans in control of the House and Senate, the Congressional Accountability Act was passed, eliminating the congressional exemption for all workplace laws and regulations. Some thought passage of the law marked the end of congressional exceptionalism through exemption. They were mistaken.

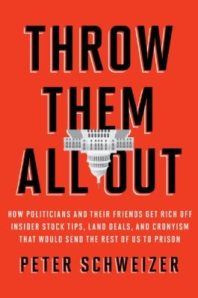

Insider trading (the buying and selling of stocks based on insider information not available to the general public) has been a violation of federal securities laws for almost 80 years. Yet it was never illegal for members of Congress. Not, that is, until a November 2011 report by CBS’s “60 Minutes” shamed Congress into changing the law to prohibit members of Congress and their staffs from trading on inside information. The report was largely based on research conducted by the Hoover Institution’s Peter Schweizer for his book, “Throw Them All Out,” published that same month. Speaking about the legislators capitalizing on their positions, Mr. Schweizer told Steve Kroft on the program: “This is a venture opportunity. This is an opportunity to leverage your position in public service and use that position to enrich yourself, your friends and your family.”

Six months after the “60 Minutes” segment with Mr. Schweizer aired, Congress passed and the president signed the Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge Act of 2012, which bans insider trading by lawmakers and their staffs. But just last week, while voters were focused on emotional issues such as immigration and gun control, House and Senate members voted to repeal a key provision of the so-called Stock Act—the one that required online posting of their financial transactions.

It’s not yet clear whether the president will sign the repeal, but it shouldn’t be necessary to take a piecemeal approach to rolling back congressional exemptions, ending them—as with the ones for workplace rules and insider trading—only when they become embarrassing. Nor will blocking exemptions here and there prevent members of Congress, particularly those who serve numerous terms, from developing a sense of privilege that makes them think they’re above the law.

America shouldn’t need to amend the Constitution to ensure that elected leaders comply with the laws of the land. But given the sorry history of congressional leadership by exemption rather than by example, a 28th Amendment doing precisely that makes sense.